Electric vs. Combustion: A Comparative Analysis of Gear Design for Commercial Vehicle Applications

The evolution of automotive technology has ushered in a new era where the traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) is gradually giving way to electric vehicles (EVs). This transition is not without its engineering challenges, particularly in the domain of gear design. ICEs and EVs have fundamentally different requirements for gearboxes, which are pivotal in translating engine power into motion. ICE vehicles require complex multi-speed transmissions to accommodate a narrow band of optimal engine speeds, while EVs benefit from simpler, fewer number of speeds gearboxes due to the electric motor’s ability to deliver consistent torque across a wide range of RPMs (Ref. 1). Firstly, we would shed some light on how ICE vehicles transitioned to EVs in the commercial segment, discussing various powertrain layouts and potential gearbox configurations. Then we will present a comparative study of different gear parameters between ICE and EV gear design and explore the impact of EV gear design on manufacturing processes. Finally, we will present a case study focusing on a 14-ton commercial vehicle (Class 7), comparing a multi-speed ICE gearbox to an EV central drive single-speed reduction gearbox. For this comparison, we assume the vehicle operates at the same output speed and torque requirements. The case study aims to provide practical insights into the application of EV gear design in real-world scenarios.

General Architecture Comparison of an ICE and EV Gearbox

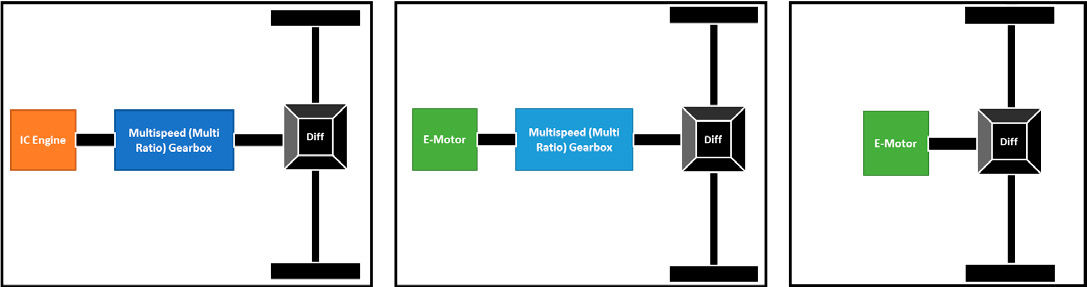

A typical ICE powertrain layout, as illustrated by the block diagram of Figure 1a, is comprised of an engine, a gearbox, and a rear drive axle. For a 14-ton vehicle, a multi-speed (5 or 6 speed) gearbox is generally necessary. Some commercial vehicle manufacturers have initiated the transition to Electric Vehicles, adopting a retrofit approach. This involves replacing the ICE with an electric motor while keeping the rest of the powertrain the same (Ref. 2) as illustrated in Figure 1b. While this approach could potentially reduce initial costs and prolong the lifei of the existing fleet, it may not yield the most efficient solution, even with adjustments to the gearbox (Ref. 2) An alternative approach would be to replace both the ICE and the multi-speed gearbox with a high-torque, low-speed electric motor to directly drive the rear axle as illustrated in Figure 1c.

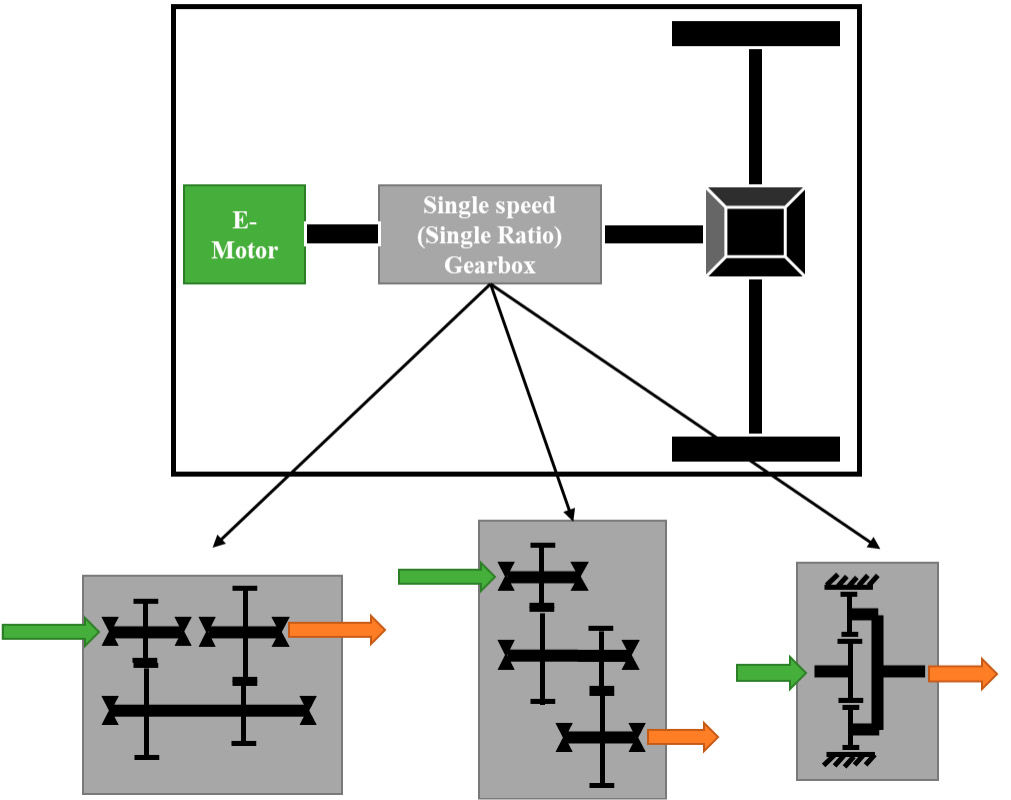

Building on the concept of optimizing electric powertrain layouts, a more effective solution for an 8–14-ton central drive layout emerges. This solution, as shown in Figure 2, uses a power-dense, high-speed (>10,000 rpm) motor coupled with a single-speed reduction gearbox. System analysis shows that a single gear ratio is sufficient to meet the startability, gradeability and top speed requirements of 8–14-ton vehicles. Because of a single reduction ratio gearbox and a high-speed motor, the overall powertrain becomes power-dense. A comparative study between the direct drive layout and a motor with a single reduction ratio gearbox showed a 300 percent weight improvement in the powertrain. Now this single-speed gearbox can further have different configurations as shown in Figure 2.

In addition to the aforementioned powertrain layouts, another viable option is the e-beam layout. In this configuration, the motor and the reduction gearbox are integrated into the vehicle axle as shown in Figure 3. This design eliminates the need for a propeller shaft and the final drive ratio becomes a part of the overall gearbox ratio. There are several ways to achieve this configuration. One possibility is a parallel axis offset reduction gearbox. where the ratio can be achieved in stages. Another option is a compound planetary system, where the ring is fixed, and the carrier is integrated into the differential case. A third option could be a combination of a parallel axis gear set with a planetary reduction set. There are numerous other configurations that can achieve the same ratio. Each of these configurations has its own advantages and disadvantages. The optimal layout can be selected based on a variety of factors, including available space, target volume and weight, cost, efficiency, and complexity.

Gear Design Comparison for ICE and EV

The primary objective of the transmission gear design is to meet the durability as per the transmission product life requirement. This is achieved by ensuring sufficient safety factors against potential failure modes. The major failure modes in transmission gears, bending and pitting, are fatigue failures that develop over time due to repeated cyclic loadings on the gear teeth during the service life of the transmission. Industrial standards like ISO 6336 (Ref. 3), AGMA 2001-D04 (Ref. 4) are generally used for the rating of gears at the design phase, so that the designed gears would have sufficient life to meet the product requirement. These rating standards estimate the safety factors by comparing the life requirement from the application to the available life calculated from the stresses under operating loads using a defined S-N curve of the gear material used. The gear’s loading pattern changes when the power source shifts from an internal combustion Engine to an electric motor. Although electric motors can provide a more stable torque input to the transmission compared to ICEs, certain characteristics of electric motors, such as bidirectional operation and regeneration, influence the loading pattern on gears. These characteristics require special attention from gear engineers to achieve the desired gear performance.

In conventional ICE transmissions, the gears rotate only in one direction, as the engine rotation direction cannot be reversed. Therefore, the primary design focus is mainly on the drive flank, which bears the load when the engine propels the vehicle. The coast flanks of the gears are loaded only when the vehicle is coasting, and these loads are typically smaller than drive loads. Exceptions to this include reverse idler gears and planet gears of planetary systems. In these cases, both flanks are loaded during normal operation as they are engaged in multiple gear meshes simultaneously. Splitter gears in certain transmission architectures are special cases where the drive and coast flank get interchanged depending on the gear selection. One of the most important features of electric vehicles over ICE vehicles is regenerative braking. During this process, the motor operates as a generator to recover the braking energy. As power flows in the opposite direction during regeneration, while the driveline rotation direction remains the same, the coast flank of the gears transmits the load. This makes the design of both drive and coast flanks equally important in EV gear design. Therefore, the overall gear reliability is the product of drive flank reliability and the coast flank reliability. Since the motor can operate in both rotational directions, reverse gear is achieved just by reversing the motor direction. This is another case where both the gear flanks transmit load in EV gearboxes.