An online forum I occasionally visit recently posted a photo of a vintage drafting board and joked about younger people not having an idea of what it was used for. Further evidence that it is time for me to withdraw from this business — my own drafting kit is older than what was pictured!

During my interview with Falk’s Chief Draftsman back in 1971, he was shocked when my answer to his “Why do you want to be a draftsman?” question was “I don’t, but you can’t become a machinery designer without becoming a draftsman first.” He agreed but found it very strange that a kid who had not even been hired yet had expectations for advancement.

I had been “drafting” for five years at that point; I actually got paid to make drawings by the school system just before public opinion turned against having in-school shop classes. Milwaukee was home to hundreds of machine shops and manufacturers. Our two daily newspapers regularly posted photos of the wonderful machines they built and shipped to a worldwide market. Everyone of those machines had hundreds of parts that someone had to make drawings of before a single chip could be made.

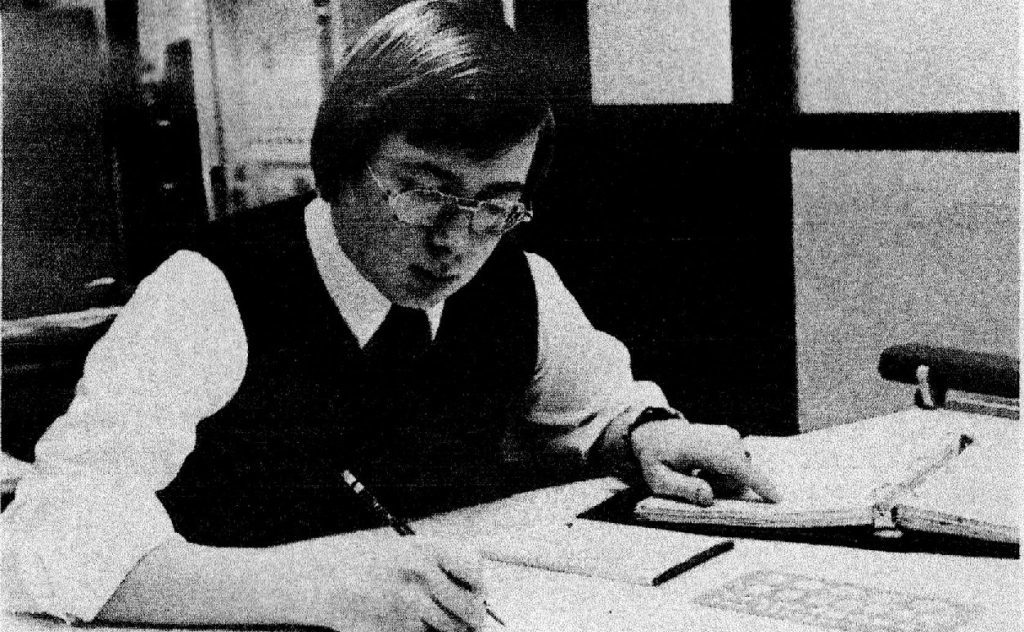

My interest was in designing machines, not just detailing the creations of others. I came into the trade well-trained in sharpening pencils, aligning the T-Square, and manipulating the triangles. I soon acquired lots of trick templates for bolt heads and other frequently used components. Drafting was an art form too; you were judged on your presentation, accuracy, and lettering as much as your speed.

No one predicted just how fast Computer Aided Drafting (CAD) would take over. Within a five-year period [probably 1980 to 1985] the number of “seats” in the drawing rooms was cut in half or more. Many great draftsmen were put out of work; designers, however, remained in demand, filling similar jobs with different skill sets and much different futures. Some of us, myself included, were reluctant adopters of the new technology. It was 1990 before my drafting board was turned into a display for print outs.

The lesson here is to master the problem solving, not the tools. If you were a good designer on the drawing board, once you got over your initial discomfort with the new “tool” you were even better without the interruptions of dull pencils and brushing off erasures. You had more time for thinking and developing new and better widgets. Conversely, if you were not well-trained in the fundamentals of your field, all CAD did was expose your weakness. Making pretty pictures of poorly thought-out parts does not help anyone. This is also true on the chip-making side of the machinery trade; CNC quickly separates the true machinists from the loader/operators.